Utagawa Hiroshige 1855 Japan, National Museum of Asian Art

Utagawa Hiroshige 1855 Japan, National Museum of Asian Art

Rice is one of the most important crops in the world. Billions of people eat rice every day as their main source of calories. For my doctoral research, I studied rice genomics and evolution. Specifically, I researched the discovery and analysis of structural variation in a population of rice varieties.

In popular science writing and on the news, we often hear about how genetic differences cause different traits in an individual. However, the specific type of genetic difference, also called a genetic variant, is not always fully explained in detail - and are hugely important! Imagine a genome is like a book; it contains the complete genetic code of an individual in the form of letters A, C, G, and T. Each individual’s book varies by a different letter here and there or an insertion of an extra couple of letters. These small differences are like typos in the book. Structural variants are another class of genetic variants; they are larger genetic differences between individuals. For example, a structural variant can be the deletion or duplication of a paragraph or entire page in the genome book. Structural variants can also cause mutations that rearrange paragraphs, pages, or entire chapters in the genome-book. They can be very large and impact many genes. Structural variants can also rearrange book portions, putting them backward or out of order. In a rearrangement, all the information is still in the book but out of order. All in all, they’re a complicated and diverse class of genetic variation!

Structural variants take many forms and are challenging to understand compared to the “typo” class of mutations, which affect much more of the genome book’s content. Therefore, structural variants can be extremely damaging and are often associated with severe and complex diseases. As a result, they are generally rare in the population, although each individual has some form of structural variation.

Many structural variants have been discovered that are responsible for important traits in domesticated plants and animals. For example, gene duplications cause differences in coat color in sheep, cattle, and pigs. In rice, a duplication increases seed size.

You can read about many more examples in the review I published

In my research, I wanted to gain an understanding greater than anecdotal examples. I decided to study structural variation as a broad phenomenon using rice as a study species.

These are two key questions I answered through my research

1. Where are structural variants in the genome?

2. How do structural variants affect gene expression?

Part I. How are structural distributed across the genome?

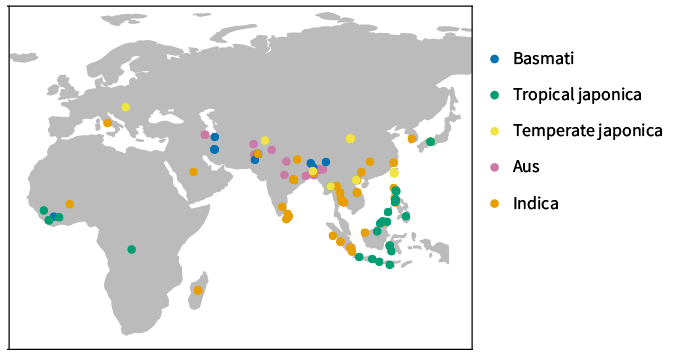

This map shows the geographic origins of each landrace sample I used in my work. Rice is a diverse species that has adapted to thrive in many types of environments and these samples reflect that diversity. The colors show the major different subtypes of rice.

This map shows the geographic origins of each landrace sample I used in my work. Rice is a diverse species that has adapted to thrive in many types of environments and these samples reflect that diversity. The colors show the major different subtypes of rice.

I discovered structural variants in a population of rice landraces using computational genomic methods. Landraces are traditional varieties of rice and have a high level of genetic diversity. These samples came from all around the world, and their genomes were sequenced in a collaborative effort of many scientists. I started the research with 4 TB of raw genome sequence data! I developed a customized bioinformatics pipeline to discover structural variants using a high-performance computing cluster.

You can checkout at the pipeline on git It took over a year to test and develop!

Using the pipeline, I discovered over 50,000 structural variants within a population of 214 rice landraces. The pipeline is complex - so let’s ge to the interesting parts - the results and what I learned about rice genomics!

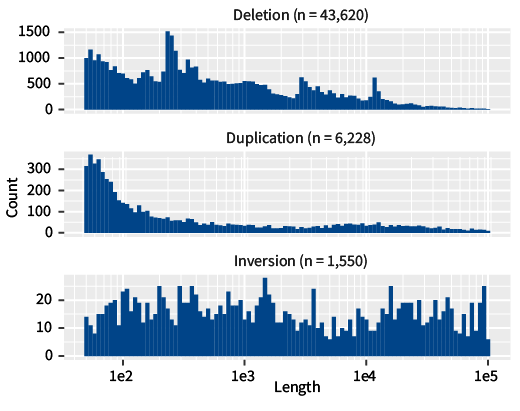

A summary of the number of structural variants and their size are measured as base pairs for three types of structural variants

A summary of the number of structural variants and their size are measured as base pairs for three types of structural variants

Most of the structural variants I discovered are deletions, and fewer nucleotides (the letters in our book metaphor) are more common for deletions and duplications. I found far more deletions than other types of structural variants because deletions are easier to identify using the particular type of genome sequence data I worked with. The pattern in structural variants’ size, however, is easily explained: the larger the variant, the more likely it is to interfere with the overall function of the organism - when larger parts of the “genomic book” get deleted, the blueprints for life don’t work.

At some point, you may have heard that most of the genome is “junk DNA,” while this isn’t entirely true, some parts of the genome are indeed much more important than others.

The genome can be divided into many different classes,in this analysis, I divided the rice genome into three different functional classes:

- Coding: parts of genes that contain the code for building proteins.

- Intron: parts of genes that do not code for proteins

- Intergenic: regions between gene

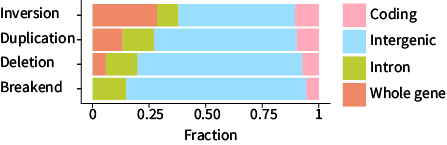

The proportion of genomic functional classes that each class of structural variant overlaps with.

This graph shows the proportion of genomic functional classes that each type of structural variant overlaps with. This graph also includes a “whole gene” category for when an entire gene (coding + introns) is affected by a structural variant. For example, the inversion row shows that ~25% of inversions overlap with whole genes. The “break end” type of structural variant is a catch-all for variants that can’t be classified as duplications, deletions, or inversions.

This graph shows the proportion of genomic functional classes that each type of structural variant overlaps with. This graph also includes a “whole gene” category for when an entire gene (coding + introns) is affected by a structural variant. For example, the inversion row shows that ~25% of inversions overlap with whole genes. The “break end” type of structural variant is a catch-all for variants that can’t be classified as duplications, deletions, or inversions.

This graph reveals several interesting patterns:

- It is clear that the majority of structural variants occur in intergenic regions—this makes sense—the rice genome is about 391 million base pairs long, and genes are predicted to cover 111 million base pairs.

- Inversions overlap far more genes than the other classes of structural variation.

These two observations are predicted from an evolutionary standpoint. If stuctural variants affect many base-pairs at a time, it is more likely to partially or completely change a gene - even remove it altogether! Deleting a gene could have severe negative impacts on the health of the organism, so we expect fewer deletions should overlap genes. On the other hand, inversions do not delete genes; they just order them differently, and the gene is more likely to still function. Therefore, inversions that overlap genes are sometimes tolerated.

Are structural variants more or less likely to occur in functional sequence?

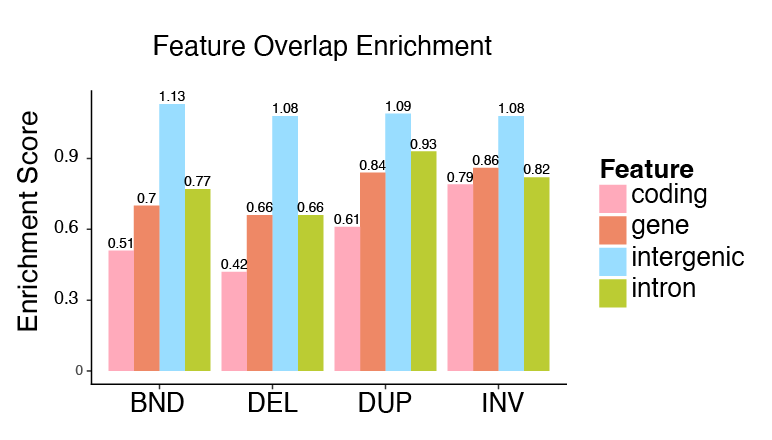

I wanted to test if structural variants are randomly distributed in the genome or if they’re less likely to occur in gene regions as predicted by evolutionary theory. To test this hypothesis, I ran a simulation to create an enrichment score. The enrichment score shows if structural variants overlap a given sequence type more or less frequently than expected by chance. The enrichment score is calculated by placing the structural variants randomly across the genome 100 times and then counting the number of structural variant base-pairs that overlap each functional class. The enrichment score is the ratio of the median random overlap base-pairs to the true total base-pair overlap.

This shows the enrichment score for each class of Structural variant: break-end (BND), deletion (DEL), duplication (DUP), and inversion (INV). The enrichment is calculated for each genomic class (referred to as a feature here). Values below 1 indicate a depletion (lower likelihood of overlap) and greater than 1 indicate enrichment (higher likelihood of overlap).

This shows the enrichment score for each class of Structural variant: break-end (BND), deletion (DEL), duplication (DUP), and inversion (INV). The enrichment is calculated for each genomic class (referred to as a feature here). Values below 1 indicate a depletion (lower likelihood of overlap) and greater than 1 indicate enrichment (higher likelihood of overlap).

The enrichment analysis shows that SVs are more likely to occur in intergenic regions and depleted from introns and exons. Interstingly, they’re also more likely to occur in intronic regions than coding regions. Again, this makes sense—coding regions are more “important” to creating the proteins than intronic regions, although the intronic regions still play a role in gene regulation and occur adjacent to the coding regions.

check out enrichment analysis code here

This post is just a snapshot of one element of my research into structural variants. As a biologist, I get most excited thinking about evolutionary processes. This kind of simple analysis demonstrates how evolutionary processes shape the patterns of structural genetic variation in genomes - which extends from rice to humans and many other organisms.